While ‘post-truth’ has become a popular catch phrase thanks to the political turbulence of the last couple of years, the crisis of trust in the connected world extends much beyond recent history. In fact, people have been grappling with multiple versions of the truth for centuries – whether in the world of brands, science, news and media, or politics.

Lately however, there’s been a particular erosion of trust in public leaders and experts amongst others, with long-held beliefs frequently being challenged by the juxtaposition of information we are exposed to in online and global events. Indeed, Edelman’s Trust barometer report finds only 29% of people globally find governmental officials credible, and just 37% CEOs.

How does this crisis of trust impact brands today, and what are the implications for brand engagement in our hyper-connected world?

Trust in brands = trust in humans

Trust is inherently emotional. In times of uncertainty, when ‘facts’, authority or other rational bases of trust are in question, people revert even more strongly to trusting their gut. The emotional principles we use to trust our fellow human beings also apply to brands.

For instance, we’re hardwired to trust familiarity. We trust people ‘in the same boat’ as us, who are as vulnerable as we are, and have as much to lose as we do. An ‘inner circle’ of friends, and even brands, can take a while to form but is always more trusted than those outside the circle; this is human nature.

We also naturally trust more in what that we can fully ‘see’, without the threat of unpleasant surprises. We need a level of transparency to feel safe, and there are classic metaphors that speak to this sentiment: seeing is believing, revealing your hand, putting your cards on the table, etc.

When we talk to people about what makes them trust or distrust a brand, it is clear that they seek the same signals that they would in other people. Isabella from Italy shares the importance of transparency at every stage. “For a company to give me complete confidence it must first of all be transparent and involve me. For example, when it comes to snacks, this means complete visibility of the company's supply chain. That means full ‘cradle to cradle’ disclosure, from its original source to my mouth.” And Ed, a 25-year-old professional in London, feels discomfited by many of his ‘anonymous’ interactions with brands, saying that he wants “to see who’s behind the screen”.

‘Behind the screen’

Interestingly, as brands operate in an ever-connected digital environment, they are becoming simultaneously more and less human, as well as more and less transparent.

The intimacy and directness of screen interactions give an illusion of dissolving differences and cause people to connect with brands as if they were human. On the other hand, anonymous, faceless interactions with technology can also feel cold, opaque and ‘unnatural’. Brands need to work at being on the right side of this fine line.

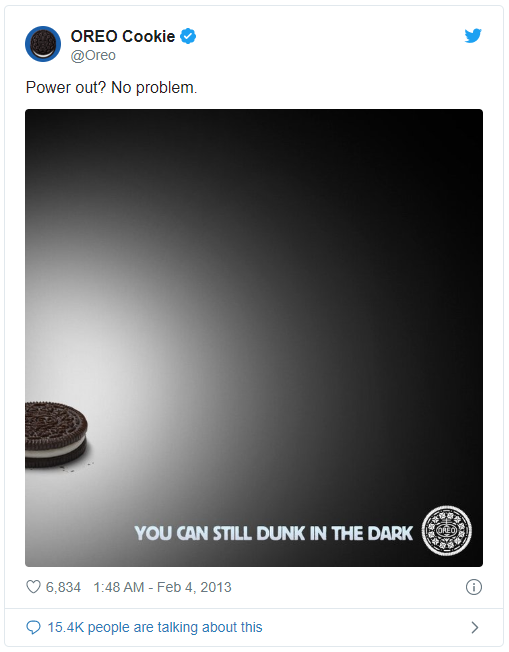

Most attempts at establishing intimacy and familiarity through digital content rely on evoking a sense of shared worldviews, camaraderie, and cultural norms. Oreo cookies classically achieved this in 2012 with a social media post that cleverly responded to a mass power outage, welcoming their customers to ‘dunk in the dark’.

Examples of genuine vulnerability and transparency are fewer – but can be much more powerful when done successfully.

Lessons from emerging markets

Inspiration for how to connect with consumers on a human level could come from an unlikely source: the adoption of technology in emerging markets tells a compelling story about how organisations can use technology to enhance trust.

Whilst people in developed markets are experiencing a dramatic shift in their ability to trust their environment, this isn’t a new phenomenon in emerging markets. Historically, the socio-political climate in emerging markets has not been conducive to trust. Corruption and inefficiency have long been ingrained in politics and livelihoods – with neither law nor social systems offering stability. While big global brands have largely rested outside this system and been regarded as trustworthy, confidence in governmental institutions has historically been very low.

However, the adoption of technology in emerging markets has had a startling effect. Many emerging markets are much more likely to trust the government with their data online – twice as many people (41%) in emerging markets are confident that the government is putting their personal data to good use compared to developed markets (20%).

We also find a greater preference for online rather than offline modes of interaction in emerging markets compared to developed markets. Indeed, mobile banking transactions have disrupted public infrastructure in parts of Africa - we only need to look at a decade of success of Vodafone’s M-Pesa in Kenya.

The difference between markets seems counter-intuitive at first glance – but what’s happened is that technology has injected reliability and integrity into perceived shady and oppressive systems. As a government allows increased access through technology, it seems to open itself to more transparency and vulnerability, and therefore becomes more trustworthy. There is an initial sense of empowerment to the people, one that developed countries first felt with the rise of social media.

In developed markets however, technology is beginning to have the opposite effect. Popular discourse points to an increasingly suspicious atmosphere of tech, big data, and the rapid expansion of automation. People are ever wary about how large corporations are using their personal data, and feeling “shut out” of opaque political and commercial systems.

“I had put a Persil promotion in my shopping basket on Amazon but hadn’t gone through buying it. Later, when I opened my gaming app, I kept receiving Persil ads. This is kind of spooky – makes me wonder about both Amazon and Persil.”

The imperative for brands

Big brands have different challenges in developed and emerging markets.

In emerging markets, there is an opportunity to use technology to help people circumvent the frictions that arise from inefficient and distrusted social and regulatory structures – it can provide easier access, simplify processes, reduce turnaround time and cost. This in itself has the impact of enhancing trust.

In developed markets, technology is currently seen as benefiting the organisation more than the individual – from chatbots to poor programmatic, the efficiencies seem to serve brands rather than consumers. The imperative for brands then, is to reduce opaqueness – to be open and inclusive when asking for data, and create positive stories of how data is being put to good use. And to employ technology that works for people, not just for the brand.

In both cases, customer-centric brands that take a transparent approach to their use of technology and truly have consumer interest at the heart of their purpose will be head and shoulders above those that do not.