This is how our pricing trilogy was born. Admittedly, it’s no ‘Lord of the Rings’ yet there’s an analogy to the epic novel: The future of civilization/marketing rests in the fate of the One Ring/pricing, which has been lost/stolen by finance for centuries/too long. Ours has an alternative happy ending: rather than destroying the (One Ring) so that it doesn’t fall into the wrong hands, ‘pricing’ is revived in the joint custody of marketing and finance.

So, let’s get started!

Chapter One: How to set the right price and the role consumer perceptions play in doing so.

Scene 1: Marketers are still defensive about pricing. Why?

The marketing team, led by their CMO, dances to the beat of ‘We are the Champions’ at their local pub in Southwest London. They are there to celebrate the phenomenal rise across all advertising metrics in their recent campaign. Meanwhile, the company’s CEO is reassuring investors about last quarter’s decline in margin. Although they work for the same company, the two C-suite members have different challenges, different targets, different perspectives.

To be fair to the scene’s starring CMO, s/he is in a precarious position, and her/his department is seen as ‘a cost’. It’s been a few decades since pricing was given to finance, so marketing considers ‘growing profit margins through pricing’ to be quite low in their list of job responsibilities. Although they know profits are the lifeblood of every company, it’s the CEO, the finance department and the investors who are held accountable.

But there is another, deeper reason for their defensive attitude: Professor Byron Sharp, in all his marketing brilliance, has been on a mission to condemn pricing power, i.e., a marketer’s ability to increase price without losing (many) customers. Professor Sharp’s comments on social media have been terse and dismissive – “You can’t affect price sensitivity”, “Don’t fall for the seductive sales pitches of pricing power” – each time reminding marketers of one of his paramount principles: perceptions don’t influence sales. So much so that there is a growing segment among marketers who have dangerously departed from logic, who believe that if you survey your category’s sub-set of brands and control for size, the data will prove that all brands – yours and your competitors’ – are perceived exactly the same way. Come again?

Scene 2: The case in favor of Pricing Power

…is a case in favor of marketing. Good marketing uses brands to solve real problems for people. A good marketer aligns their brand’s interests to those of the consumer and invests in their brand as a value-producing asset. This value creates demand for which consumers are willing to pay. Any ‘extra’ value creates ‘greater’ demand for which consumers are willing to pay ‘more’.

Being blessed with pricing power doesn’t authorize the good marketer to launch a disorderly and unjustified price increase. It rather gives them a joystick to control their price elasticity.

Have you got ‘it’? If your price changes, and you can keep the demand for your product (almost) intact, then yes, you do. If your demand drops less than your competitors’, you have a higher pricing power than they do. And that’s when you enjoy the below benefits, as Kantar meta-analysis of thousands of brand cases over the last two years has proven:

- Consumers are willing to pay up to double for your brand vs. an alternative

- You’ve earned a 4% advantage on your brand value change last year only

- Your improved pricing power fueled your growth at twice the rate of those brands that lost pricing power

Scene 3: What does it take to achieve pricing power?

Rao’s Homemade pasta sauce is not your $0.99 ragu. Priced at the top end of the price spectrum – at $8.99 – Rao’s is four to five times more expensive than private label brands and is largely seen as an alternative to going to a restaurant. Which became a reality during Covid-19 when Rao’s created the restaurant experience in consumers’ kitchens. Demand soared. The stressful financial conditions in the market continued, but Rao’s sales remained unaffected. Demand further soared. On August 7, 2023, Campbell’s Soup Company acquired Rao's Homemade pasta sauces for nearly $2.7 billion.

What gave Campbell’s the confidence that Rao’s would remain resilient among future consumer spending cutbacks? In the 6 years under Sovos Brands, Rao’s volume grew, but its value grew even faster. Campbell’s didn’t buy Rao’s for its distribution nor for its awareness levels; both metrics are at a disadvantage compared to its peers in the category. What swayed investors was Rao’s associations with fine dining at home and its ability to command a price premium when all hell broke loose. Pricing power has steered Warren Buffet’s decisions for decades. The American business magnate and investor declared, “The single most important decision in evaluating a business is its pricing power”.

Feeling warmer towards pricing power now? Let the data guide us on what pricing power is linked to and what it isn’t:

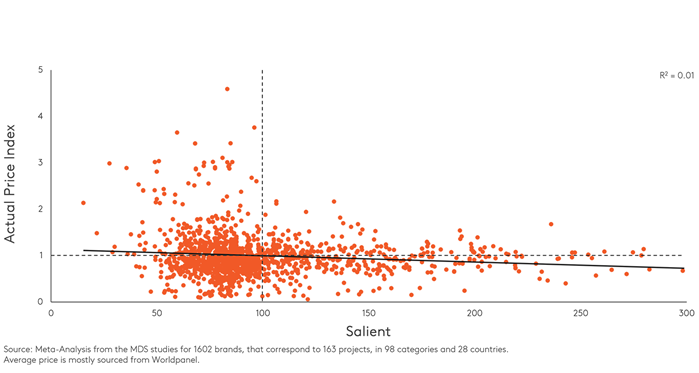

1. Salience – being remembered at critical decision-making moments, so another word for mental availability – contributes almost nothing to Pricing Power.

Actual Price Index and Salient metric show no relationship

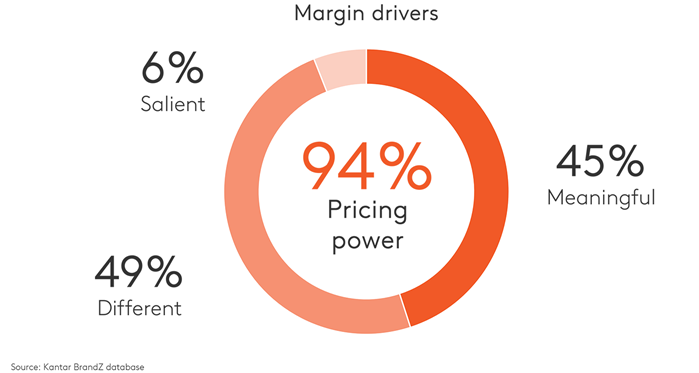

2. Meaningful Difference – meeting emotional and functional needs and standing out from competitors – accounts for 94% of a brand’s Pricing Power

Meaningful Difference drives value: price power

Scene 4: What’s your game? Volume or margins?

Before you sit down to set your price, you should figure this out.

Inspired by Philip Kotler’s pricing strategies, fresh out of university marketing graduates dream to remain premium-priced in eternity. But soon into their first job, they get sucked into marketing’s (un)conscious bias of volume vs. profit. They develop a fixation with volume and revenue, an overreliance on discounts and – by extension – an apathy towards the bottom line.

So much so that most brand equity research focuses solely on creating demand to drive volume share and penetration. Most, but not all. Kantar believes that a brand's pricing power is at least as important as demand power and uses the ‘concept of worth’ to model it. This surfaces a critical piece of information on consumers’ perception of your brand: whether it’s overpriced or whether, in their minds, it’s worth more than you are currently charging. Imagine ‘relative price’ and ‘willingness to pay’ plotted on a chart to steer your thinking process on the ‘price itself’; more on that in the second chapter of our trilogy.

Now back to the price-volume conundrum. As a good rule of thumb for a brand, you can use a price elasticity of two, meaning that for a 10% increase in price, expect a 20% fall in volume and vice versa. Brands and categories have differing prices though, so the first step is to understand the relationship between Price, Price Elasticity and Pricing Power for the category.

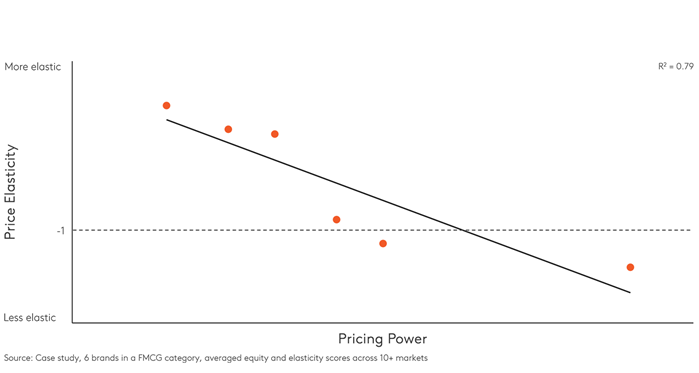

In this chart, we've plotted brands from an FMCG category. For each, we first examined price and volume sales over time to understand their relationship, the price elasticity. We see that the brands with higher Pricing Power have better price elasticity, meaning that they lose less volume at higher prices.

Higher Equity (as measured by Pricing Power) relates to lower Price Elasticity

Analytics can help you explore that link between Pricing Power and price elasticity for your category and brand, and hence model possible market outcomes, depending on whether you are trying to optimize volume or margins.

Scene 5: Is my price giving off the wrong signal?

Although markets are pretty competitive, our evidence suggests that some brands sell for above expected price. Yes, a few of them are better quality, others simply have a better image that influences our perception of quality to justify a higher price. “Very few things in life [are bought] entirely on function”, Jeremy Bullmore and Stephen King of J. Walter argued back in the ‘80s, when the economy wasn’t in its best shape either. “[Consumers] certainly want function, but they want function plus. And it’s this plus that makes all the difference [to consumers’ choice].”

Over the last 50 years, a lot has changed in the marketing toolkit, but sales promotions’ popularity has remained a stubborn constant. In fact, UK’s most recent IPA Bellwether report revealed an increase of over 13% in promotional activity. Unwarranted considering the proportion of consumers saying that they are primarily price-driven has not changed since 2014. That was the inaugural year Kantar BrandZ asked a single, simple question about primary motivations: "Do you always choose the same brand, do you choose from a number of brands, or do you always go for the cheapest?" For the majority of the categories, the proportion of price-driven consumers has since remained, on average, around one-third.

But how damaging is it to set the price too low, even if it’s intended to be short-lived? And equally, can a too-high price be damaging?

Set it too low and you decimate your profits, you effuse low quality, you taint your brand equity. Even when it’s considered a reversible action, it can dangerously set new expectations from your trade partners. A price set too low is an awkward ‘own goal’ moment that lingers; a wrong position and initial misjudgment that costs you the World Cup.

Set it too high and you miss out on volume and revenue. As a result, your supply will likely be greater than your demand, and you’ll get stuck in a cycle of the excess inventory (or else, higher unit costs). A price set too high innately signals better quality, but also sometimes puts up a ‘not for me’, ‘not for often’, ‘let’s keep for our golden wedding anniversary’ consideration/ purchase barrier for consumers.

Price setting is so central to the success of the role of the CMO (and the business as a whole) that Les Binet’s motto “If pricing is wrong, all other marketing efforts are futile” at Kantar’s last Ignite event held no hint of hyperbole.

Scene 6: Good pricing can offset lost penetration. Bad pricing doesn’t help your market share.

We conducted two more data investigations to understand the interplay between price, equity, penetration, and market share. Here’s what we found out:

1. Investing in brand equity and aligning pricing to pricing power has a positive impact on your brand’s value. We compared brand value change over 4 years between brands that improved their global average pricing power vs. those that lost some of their pricing power. The former grew at twice the rate in that time – adding 67% to their brand value compared to just 33% for brands in the latter group. We looked at a variety of effects and this – the pricing power effect! – is one of the strongest influences on brand value that we found. It’s so strong in fact, that even if a brand loses some penetration over this period, a gain in pricing power more than offset this. Pricing at the right level is a better way to maintain profitability and sustain business value.

2. Setting the price too low has a negative impact on your equity. We examined more than 15 over time observations that exist in the BrandZ database for the same category. Of these, 10% were more recently perceived as less expensive than their competitors, i.e., their price was too low. Although these brands marginally gained penetration, their share remained unchanged, and their equity dropped. This loss was most marked for brands that started with stronger equity. Weaker brands gained a little from moving into more appropriate pricing 'frame' for consumers.

Scene 7: It’s time to plunge into your moment of truth.

Pricing is the moment of truth. Mark Bergen, one of the greatest marketing thinkers of our generation has repeatedly recognized the importance of price and that singly unique moment where we discover whether our offer is going to meet with customer demand. He says: “Pricing is the moment of truth. It’s where all your marketing strategy really meets that final decision point with your customers.”

At exactly that moment, a marketer’s hard work is put to the test: does your brand positioning (i.e., how you show up in the market) justify your pricing strategy? Whichever way you get to the price itself, be that a simple survey, conjoint analysis, or shinier tools that pinpoint your optimal price sweet spot, the uncertainty around the moment of truth will only clear up once you’ve consulted your customers.

But as we conclude our price-setting activity chapter, there are two things we can be certain about:

1. Pricing is a two (wo)man job. The finance team has the desire and the authority to set the price based on the costs of the volume sold, competitor pricing, gross margin potential etc. and yes, they juggle the interplay between these financial factors in Excel with enviable dexterity. But marketers know the consumers best; they get the ‘concept of worth’, and they fathom how perceptions can influence sales. They go beyond book value to the intangible value that derives from the brand. They are the titular connectors between the tangible and the intangible, and unless they are there too, the price ain’t going to be right.

2. Pricing is a Sisyphean task; it might go into hiatus for a while, yet it never really ends. But unlike Sisyphus, who was sentenced to do an incessant job as punishment for cheating Death, marketers ought to fight their way back to it - then and only then can marketers maximize their impact on the bottom line. With pricing authoritatively in their toolkit, CMOs will empathize with the CEO challenge and gently pull a big C-suite influence lever. That lever merits a permanent seat in the boardroom, right there, next to their finance partner.

Discover how to keep a permanent tab on pricing power with Kantar BrandTek equity and tracking solutions. Get in touch to find out more.